Portions of this text underwent peer review by four independent reviewers for Water Policy,

the official journal of the World Water Council. The text was reviewed in its entirely by the

following expert consultants: Ivor van Heerden, former Director of the Louisiana State

University Hurricane Center and co-author of The Storm: What Wrong and Why During

Hurricane Katrina (Pelican, 2006), Dr. Stephen Nelson, Dept. Earth & Environmental Sciences,

Tulane University, and H.J. Bosworth, Jr. P.E., Research Director, Levees.org.

Introduction

The failure of levees and flood walls during Hurricane Katrina in 2005 has been termed

“the worst civil engineering disaster in United States history.” Lt. Gen Carl Strock,

Commander of the Army Corps of Engineers, the agency responsible for the system’s

performance since Hurricane Betsy in 1965, referred to the levee protection as a

“system in name only” when he presented the Army Corps’ investigative report to

Congress and the American people on June 1, 2006.

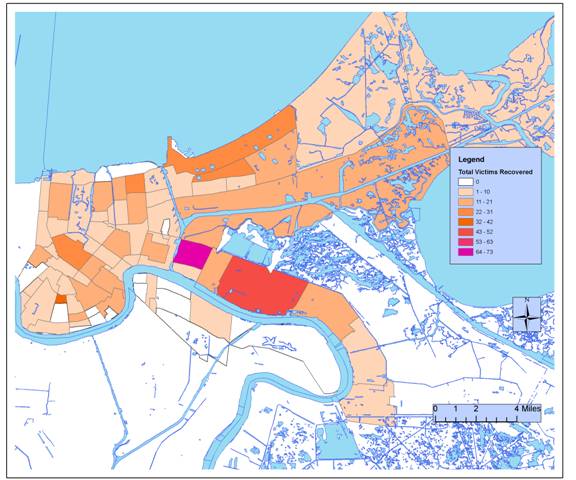

During the morning of August 29, 2005, hurricane storm surge broke through and over

levees and flooded 80% of New Orleans and 100% of St. Bernard Parish located downriver

of the city. The damage caused by the levee breach event dwarfed those of all previous U.S.

disasters. Most of the federal spending post-Flood went toward relief, not rebuilding.

Charitable giving also outpaced that for previous disasters. Congress authorized emergency

spending to rebuild the flood protection system, totaling $14.5 billion. But the ‘flood control’

system has been reclassified to that of “risk reduction,” somewhat less that the original flood

protection purpose of the hurricane protection system authorized by Congress in 1965.

Initially folk were slow to return to New Orleans and many felt that it would never fully recover. However, the pace of return has sped up in the last few years. For instance between 2010 and 2013, the Census Bureau population estimates show an increase in the New Orleans population of 10 percent. Neighborhoods most heavily flooded by the levee failures continue to grow the fastest. Most of these heavily damaged areas experienced double-digit percentage increases between 2010-14, including growth rates of more than 30 percent in Fillmore, Holy Cross, Lakeview, Lower Ninth Ward, Pontchartrain Park, and close to 30 percent in Pines Village and Read Blvd West. This year, ten of the “sliver’s” historic, naturally elevated east bank neighborhoods have reached 100 percent of their June 2005 pre-Katrina number.

The failure of levees and floodwalls is presented here as six separate chapters designated principally by their location. We also present how this catastrophic failure of a federal government project, The New Orleans Hurricane Protection System, changed America as we know it and how the American people are safer today than before Katrina arrived. There is also a “myth buster” section to debunk popular, but incorrect assumptions about New Orleans and the people who live call this home.

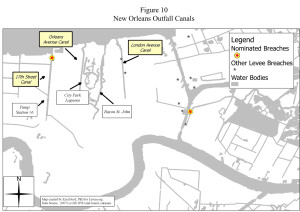

17th Street Canal Breach

The day before Hurricane Katrina’s storm surge arrived, the Lakeview neighborhood was a densely populated area of primarily middle- to upper-class, white homeowners. Homes filled the area right up to the levee of the 17th Street Canal which was, and still is, the largest and most important drainage canal for the city of New Orleans. Operating with Pump Station 6, at that time the largest pump station in the world, it could move up to 9,200 cubic feet of water per second. Huge 50-year-old oak and pecan trees grew at the base of the canal’s levee and throughout the neighborhood.

On August 29, 2005, between 8:45 and 9:45 a.m, a concrete levee monolith (30-foot long section of flood wall) failed and released flood water into Lakeview. At the moment of failure, the water level was about 2.6 feet lower than the top of the wall, which means that the pressure (weight of the water) did not exceed the design safety limit. The breach quickly expanded into a 450-foot wide gap through which storm surge water poured, killing hundreds (directly and indirectly), destroying hundreds of residences and causing millions of dollars in property damage. The flooding extended far beyond Lakeview and also flooded Lakewood North and South, Broadmoor, Mid City, Old Metairie, Leonidas, Gert Town, Hollygrove, portions of Uptown and Carrollton, and more.

Today, the adjacent lots are completely void of homes, buildings and trees. Foundations or slabs of concrete where homes once stood are all that remain. The repaired breach site now consists of a different, sturdier design called a T-wall. Three times more expensive to build, the new wall can be easily differentiated because of its different texture, color and thickness.

In the photo below, the new repaired flood wall, from a bird’s eye view, is also more than a foot thicker.

How did this happen?

In 1965, Hurricane Betsy demonstrated that a major hurricane could overtop the earthen levees of the 17th Street Canal. The Army Corps of Engineers initially reviewed five plans to deal with this problem, eventually narrowing their recommendations to two plans, as is common practice. Right-of-way was a significant hurdle, as homes were built very close to the levees. For every one foot of levee height, the Army Corps needed three horizontal feet of land base. Eventually, the Army Corps of Engineers recommended two cost-effective plans to the local sponsor (Orleans Levee Board) to remedy the flood threat: 1) (parallel plan) strengthen and raise the height of the levees by installing flood walls; 2) (gates plan) install floodgates at the canal’s mouth at the lakefront. Records show that the Corps felt both plans were equally reliable. (It is instructive to note that the gates plan did not include auxiliary pump stations like those in place today).

Since the cost for each approach was about the same, the Corps ultimately elected to raise the levees using flood walls because the local sponsors (Orleans Levee Board and the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans) preferred it. Among other concerns, the OLB and SWB viewed the floodgates plan as incompatible with their interior drainage responsibilities. Post-disaster studies conclude that the breach was due to driving steel sheet pilings for the walls to depths that were too shallow and shaving soil off the bank. Tragically, in recommending I-walls with such short sheet pilings, the Corps had relied upon a poorly executed and misinterpreted study it had conducted near Morgan City between 1985 and 1988. At a savings of $100,000,000, the Corps wrongly concluded it could short-sheet the steel pilings of the 17th Street Canal, driving them to depths of not more than 17 feet instead of between 31 and 46.

The Army Corps’ levee design and construction blunders doomed the citizens of New Orleans. In hindsight, it is clear that there was no question that the 17th Street Canal would fail. The only questions were when and where, and on August 29, catastrophic failure occurred on the Orleans side of the 17th Street Canal when the levee supporting the steel and concrete flood wall slid sideways–trees and all–on top of the organic and slippery soil remnants of an ancient bayou.

The breach of the 17th Street Canal has been called, “the single most disastrous failure site for the Corps” in terms of the damage that this single breach caused and the death it inflicted. In addition to flooding Lakeview, it flooded the region of the city with the most people, property and infrastructure, including the Central Business District.

Post-Katrina investigators observed that there was some minor movement of the flood walls on the Jefferson Parish side. But these levees were in better shape mainly due to the existence of more earth and of a paved road making the area more compact and stable.

The home at 6926 Bellaire Drive near the site of the 17th Street Canal breach. Before the Flood (11/22/00) and after (9/30/2005). Photos/Roy Arrigo

In January of 2008, Federal Judge Stanwood Duval of the US District Court for Eastern Louisiana held the US Army Corps of Engineers responsible for defects in the design of the concrete flood walls constructed in the levees of the 17th Street Canal; however, the agency could not be held financially liable due to sovereign immunity provided by the Flood Control Act of 1928.

Post-Katrina, the Army Corps has strengthened and enhanced the reliability of the levees and flood walls of the 17th Street Canal in the following ways: 1) gates with massive pump stations have been installed at the canal’s mouth to Lake Pontchartrain; 2) the Army Corps has designated a “safe water” level in the canals which is lower than the height of the canal wall; 3) the levees have been strengthened by mixing soil with cement and pumping the slurry back into the levees; and 4) relief walls that act as “warning gauges” have been installed.

London Avenue Canal East Breach

Before the 2005 Flood, the adjacent area to the breach site of the London Avenue Canal was a thriving, mixed neighborhood of white and African-American, middle-class homeowners. Oak, pine, cypress and pecan trees grew throughout the neighborhood and also at the base of the canal’s levee. Today, the adjacent land is largely vacant of homes, buildings and trees. The flood wall at the repaired breach site now consists of a different, sturdier design called a T-wall. Three times more expensive to build, one can easily see the difference in the walls because of the different texture and color.

The London Avenue Canal flood wall failed on both sides, an obvious testament to how egregiously unreliable the flood walls were before Katrina arrived in 2005. After Hurricane Betsy, the Army Corps of Engineers recommended two plans — raising the height of the levees by installing flood walls or installing floodgates at the canal’s mouth at the lakefront. The Corps felt both alternatives provided equally sufficient storm surge protection. (Unlike the gates built post-Katrina, these proposed gates in the 1980s did not include auxiliary pump stations.)

Since raising the heights of the walls was three times more expensive than the gates plan, the Corps recommended the latter in keeping with its congressional mandate to choose plans with the most favorable cost-benefit ratios.

Meanwhile, the Orleans Levee Board (OLB) and the Sewerage and Water Board (S&WB) had several concerns, but they mainly feared that the cheaper gates-only plan was incompatible with their interior drainage responsibilities. So, in 1991, the OLB and the SW&B asked their state congressional delegation to pressure Congress for the more expensive “higher walls” plan. The lobbying effort worked, and the Army Corps was ordered to raise the heights of the canal walls. Pressure from the Louisiana delegation succeeded while the Army Corps ignored local levee boards.

On August 29, 2005, at about 9:00 a.m, to your immediate left, several concrete levee monoliths (30-foot long section of flood wall) failed, sending torrents of water and sand into the adjacent neighborhood. The home that once stood on this lot was picked up, rotated nearly 180 degrees, carried 100 feet and deposited in the middle of Warrington Drive (to your right). In the photo below, the white spot in the water (left and upward from photo center) is natural gas bubbling to the surface from the gas line that once fed the house at 5000 Warrington Drive.

Note the address over the door below is ‘5000’ which is succinct proof this house once stood in front of the breach site.

Storm surge water poured through the gap, killing hundreds (directly and indirectly), destroying homes for as far as the eye could see and costing millions in property damage. The floodwaters affected more than a dozen residential neighborhoods in Gentilly.

At failure, the water level in the canal was about 2.5 feet lower than the top of the wall and represented about 50 percent of the design load it was designed to hold.

Post-disaster studies conclude that steel sheet pilings were driven to depths that were too shallow. Tragically, in recommending the I-walls with such short sheet pilings, the Corps made a recurring mistake and relied upon its poorly executed and misinterpreted study conducted near Morgan City in 1988. Again, at a savings of $100,000,000, the Corps wrongly concluded it could drive the steel pilings of the London Avenue Canal to depths of not more than 17 feet instead of between 31 and 46.

Also critical to the failure mechanism was that the Army Corps, in designing the flood walls, did not take into account a 50-foot thick sand layer, just below the soil. This very permeable soil allowed seepage under the levee that resulted in a blowout and collapse of the flood wall. TEAM LOUISIANA, in their forensic study, determined that this oversight meant the levees’ factor of safety was only 50 percent.

The London Avenue Canal was doomed to fail when storm surge entered it. Sand, lots of it, can be seen in this photo below. The home formerly at 5000 Warrington is in the middle of the photo.

According to the Corps-sponsored Interagency Performance Evaluation Task force, the catastrophic breaches of the London Avenue drainage outfall canal represented a failure of the system to meet design objectives; a conclusion also reached by the ILIT and TEAM LOUISIANA forensic investigation teams.

In January 2008, Federal Judge Stanwood Duval of the US District Court for Eastern Louisiana held the US Army Corps of Engineers responsible for defects in the design of the concrete flood walls constructed in the levees of the London Avenue Canal; however, the agency could not be held financially liable due to sovereign immunity provided in the Flood Control Act of 1928.

Post-Katrina, the Army Corps has strengthened and enhanced the reliability of the levees and flood walls of the London Avenue Canal in the following ways: 1) gates with massive pump stations have been installed at the canal’s mouth to Lake Pontchartrain, 2) the Army Corps has determined a “safe water” level in the canals which is lower than the height of the canal wall, 3) steel sheet pilings were driven to deeper depths, and 4) relief walls that act as “warning gauges” have been installed.

London Avenue Canal West Breach

At about 8:00 a.m., a concrete levee monolith (30-foot long section of flood wall) failed near Robert E. Lee Boulevard, directly flooding the Lake Vista neighborhood of New Orleans, a primarily white, middle-class neighborhood. The water also flooded Bayou St. John and Mid City.

One block from the breach site, on Charlotte Drive, an elderly couple named Harvey and Renee Miller did not hear the flood wall breaching two blocks away, but Renee was the first to notice dark spots on the wall-to-wall carpeting. Water was coming up through the first floor, which was 10 feet above the ground.

Harvey and Renee rushed to the window and watched in disbelief as water surged down the street like river rapids. They stood stunned and watched in further disbelief as–in a matter of seconds–a Cadillac was picked up, carried down the road and deposited next to a tree. But there was no time to watch further because water was already a foot deep in the house, and they had to get upstairs. They brought everything they could up to the second floor. On Harvey’s last trip downstairs, the water was up to his chest. (When the couple returned a month later, the Cadillac still sat nose down against the tree.)

About an hour earlier, three-quarters of a mile south of this breach, the canal wall had also failed for similar mechanical reasons. Incredibly, the canal walls had failed on both sides of the London Avenue Canal. This is a remarkable testament to the weakness of the flood walls.

Two days later, Harvey and Rene and their dog were rescued by boat and then all of them were separated by hundreds of miles in the evacuation process. They were all joyfully reunited on Friday and on Monday September 5, they moved to St. Louis, Missouri, and never returned.

The reasons for the west side failure of the London Avenue Canal are similar to those for the 17th Street Canal, namely the failure on the part of the Army Corps to drive steel sheet pilings down to proper depths. An in-depth discussion of the decision-making that resulted in the “short sheeted” steel pilings can be found in the section entitled “17th Street Canal Breach.”

Post-Katrina, the Army Corps has strengthened and enhanced the reliability of the levees and flood walls of the London Avenue Canal in the following ways: 1) gates with massive pump stations have been installed at the canal’s mouth to Lake Pontchartrain; 2) the Army Corps has designated a “safe water” level in the canals, which is lower than the height of the canal wall; 3) sheet pilings were driven to deeper levels; and 4) relief walls have been installed that act as “warning gauges.”

Breaches of the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal (locally called the “Industrial Canal”)

The area now known as the historic Lower Ninth Ward mostly sits on Mississippi River levee material. In the mid-1800’s, working-class African Americans and immigrant laborers from Ireland, Germany, and Italy seeking affordable housing migrated to the area. In this rural setting, residents enjoyed ready access to fishing grounds and grew okra and other vegetables. The Ninth Ward was born In 1852 when three municipalities joined to create the modern city of New Orleans. The Ninth Ward grew into a unique neighborhood with intergenerational and familial relationships across decades.

In 1923, a 5.5 mile long Industrial Canal (Inner Harbor Navigation Canal) opened, connecting Lake Pontchartrain to the Mississippi River. Equipped with a massive lock, the canal allowed large cargo ships and barges access to river wharves. The canal is 30 feet deep and 300 feet wide at its lake end and about 150 feet at its lock end. The Industrial Canal separated eastern New Orleans from the rest of the city and split the Lower 9th Ward neighborhood away from the Upper 9th Ward.

In September 1965, Hurricane Betsy pushed storm surge into the Industrial Canal and the east side canal levee breached in the same general area where it would breach again 40 years later during Hurricane Katrina. In 1965, eighty percent of the Lower Ninth Ward area went under water. The city reported an official count of eighty-one deaths. Up until the devastation in 2005, the Lower Ninth Ward retained its heterogeneous population, including socio-economically disadvantaged and middle class residents, predominantly African Americans. Fats Domino—often credited with releasing the first rock ’n’ roll record—was born and raised here. He almost died in the 2005 levee Flood.

Immediately preceding Katrina, the area in front of the east breaches of the Industrial Canal was a dense, thriving neighborhood of primarily African-American, lower- to middle-class homeowners. Houses in this neighborhood were built right up to the canal levee and were shaded by huge oaks, cypresses and pecans.

On August 29, 2005, at about 4:30 a.m., water blew out a sandbag plug where the CSX Railroad crosses the northern arm of the canal on the west side, starting to flood New Orleans East subdivisions. (A gate was missing because it had been damaged by a train derailment and was still under repair.) About 30 minutes later, a larger breach developed south of the railroad crossing, also on the west side, near the Florida Avenue Bridge. This major breach flooded the eastern part of Orleans Metro, south of the Metairie Ridge.

At about 7:30 a.m., the east side of the Industrial Canal breached when the Army Corps’ lock gauge was reading about 12.5 feet. The overtopping of the canal wall, built four feet too low, had scoured a trench behind the wall, causing failure.

Many Lower Ninth Ward residents reported hearing an explosion. Three blocks away, storm surge chased Robert Green, his brother-in-law, Jonathan, and five helpless people to their attic: his 73-year-old, Parkinson’s-stricken mother, Joyce; his 60-year- old, intellectually disabled cousin; and three tiny granddaughters – Shaniya, age two, Shanai and Shamiya, four. Joyce and Shanai would not survive after the house floated a city block and broke up against a tree at 1617 Tennessee Street. Little Shanai was buried on November 19, and Joyce Green on January 14, 2006.

The breach, which widened to nearly 1,000 feet, occurred partially because the Army Corps did not understand survey data and used the wrong base elevation. Within the hour, a section of the I-wall just south of the blue-painted Florida Avenue Bridge breached not far from a Sewerage and Water Board pump station. Experts disagree over the cause and time of this much smaller breach, but in the end the issue was moot. Floodwaters from both breaches combined and submerged the entire Lower Ninth Ward with between 6 and 12 feet of water, killing hundreds directly or indirectly, and destroying homes and infrastructure.

The water from the two east breaches of the Industrial Canal also flowed into the cities of Arabi and Chalmette in adjacent St. Bernard Parish. Floodwaters from two breaches on the western side of the Industrial Canal combined with floodwaters released from the 17th Street and London Avenue Canals to flood most of New Orleans’ main basin, the portion of the city with the most people, property and infrastructure.

Automobiles left upside down at the corner of Deslonde and N Prieur Streets in the Lower Ninth Ward. January 26, 2006. Photo/Andy Levin CLICK TO ENLARGE

Before the storm, an empty barge owned by Ingram Marine had been moored across from the area that would become one of the breach sites. At some point it came loose, and after Katrina’s winds and the eye had passed into Mississippi, the barge was pushed across the Industrial Canal. It then floated through the southeast breach and was deposited in the Lower Ninth Ward. In January of 2011, federal Judge Stanwood Duval ruled that the mooring company responsible for the barge was not liable for damage. In concluding his 42-page opinion, Duval wrote:

“The horror and tragedy of the flooding that occurred in the Lower 9th Ward is one that must not be taken lightly. The testimony of those caught in the maelstrom is heartbreaking and defies belief that such a catastrophe could occur. However, there is overwhelming evidence that the (barge) did not cause in any manner cataclysmic flooding of the Lower 9th Ward.”

The barge became an icon after the storm, illustrating the violent flooding. When the area re-flooded during Hurricane Rita on Sept. 23, the barge refloated and was deposited on top of a school bus.

The Industrial Canal breached in two locations on the west side due to overtopping and erosion. The locations directly affected were commercial; however, the flooding extended to nearby residential neighborhoods, including the Upper Ninth Ward, Pontchartrain Park, Gentilly Woods, St. Claude Avenue, St. Roch Avenue and more.

Post-Katrina studies concluded that the southeast I-wall and the northwest I-wall were overtopped by floodwaters–a situation that was exacerbated by the surge-amplifying “funnel” created by levees along the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, both deep-water navigation channels. This funnel phenomenon was first predicted 50 years ago by Kenneth J. LeSieur, chair of a citizens’ committee on flood control. In a report, the group observed that the Army Corps’ proposal for a levee along the south shore of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet and along the north shore of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway would form a funnel, channeling all hurricane surges and wind-driven water into the Industrial Canal. Even in 1965, this probability was recognized as a critical and fundamental flaw. This phenomenon was also highlighted by the LSU Hurricane Center, starting about five years before Katrina arrived. But the Army Corps always denied that there was any funnel effect. In 1973, Corps Commander H. Lee Butler while working at the Waterways Experiment Station in Vicksburg, believed that the models predicting it must have been flawed.

Failures occurred when the water level was estimated to be 1.7 feet above the tops of the flood walls and levees. Out of the 50 estimated levee breaches system-wide, the majority can be attributed to overtopping and erosion. In other words, as the water overtopped the flood walls, it caused waterfalls that resulted in erosion of the earthen levees. The sheet piles, which were far too short, were insufficient to hold up the flood walls. Once the soil levees on the landward side were scoured to a depth of about three feet, the flood walls collapsed, initiating catastrophic flooding.

Today, the adjacent land of the Lower Ninth Ward is largely vacant of homes and buildings. Many foundations or slabs where homes once stood are all that remain. All trees have been removed either due to the initial flooding or removal by governmental agencies post-Katrina. An exception is the Make It Right project, spearheaded by actor Brad Pitt. A majority of the 150 homes planned to be built by the Lower Ninth Ward breach site have been completed.

Below are before and after photos of 1825 Forstall Street, four city blocks from the breach site. Note the tidy yards, the density and the mature pecan in the background. Afterward, note the devastation and that the pecan is gone. Such deforestation changed the texture of neighborhoods here and throughout the city.

A home on Forstall Street, four blocks from the breach site. March 2005 and October 2005. Photos/Roy Arrigo

Post-Katrina, the Army Corps has strengthened and enhanced the reliability of the levees and flood walls of the Industrial Canal in the following ways: 1) a gate, called the Seabrook gate, has been installed at the canal’s mouth to Lake Pontchartrain; 2) the levees have been strengthened by mixing soil with cement and pumping the slurry back into the levees; and 3) relief walls that act as “warning gauges” have been installed.

Most importantly, the Army Corps–at a cost of $1.1 billion–has built a storm surge barrier near the confluence of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW) and MR-GO. Called the Lake Borgne Surge Barrier, it’s more than a mile long, has two 150-foot-wide navigable floodgates on the GIWW and a 56-foot-wide gate on Bayou Bienvenue. With the Seabrook gates, the barrier is designed to keep storm surge from entering the Industrial Canal.

Breaches of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway

The residential region known locally as “New Orleans East” was flooded during Katrina mainly due to multiple breaches in the levee along the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW). Eighty percent of the neighborhood–primarily middle- to upper-class, African-American homeowners–was flooded by more than six feet of water; almost half the region sustained more than eight feet. The flooding did enormous damage to the neighborhoods of Pines Village, Little Woods, Plum Orchard, Read Blvd East and West, Village de l’Est, Venetian Isles and Lake Catherine.

New Orleans, LA, Sept. 14, 2005 — Six Flags Over Louisiana remains submerged two weeks after Hurricane Katrina caused levees to fail in New Orleans. Bob McMillan/FEMA Photo CLICK TO ENLARGE

Levees breached along the GIWW for different reasons than the other major breaches in New Orleans. But first a little history.

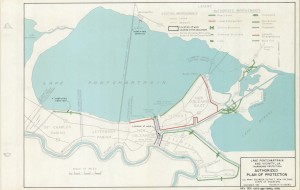

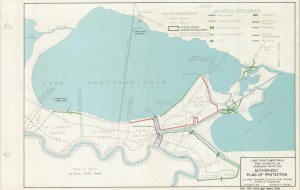

In the early 1900s, this region was mainly wetlands and cypress swamp snaked with natural bayous. There was little development, with the exception of the long, narrow ridge of higher ground along Gentilly Road. This followed the natural levee of an old bayou and the higher ground along Lake Pontchartrain. After Hurricane Betsy in 1965, Congress ordered the Army Corps of Engineers to be in charge of designing and building the hurricane protection for the greater New Orleans region. As you can see in the Authorized Plan of Protection, this included building new levees along the lakefront, levee enlargement along the GIWW and a flood wall along the Industrial Canal.

The region saw rapid growth in the 1960s and 1970s. Many new subdivisions were developed to cater to those who preferred a more suburban lifestyle but were open to remaining within the city limits of New Orleans. Historians question why the area farthest east was developed, since it was viable wetlands and because ringing this region with levees did nothing significant toward protecting the city. What expansion accomplished was to increase the amount of land that could be developed, and it was a reason for the Army Corps to expand the size of its project.

Eastern New Orleans flooded during Hurricane Katrina for two reasons. One reason was because portions of the levees along the GIWW were filled with sand or erodible materials instead of good, thick Louisiana clay. This can only be explained by lax quality control on the part of the Army Corps of Engineers and/or their contractors during the building phase. A second reason the region flooded badly was the “funnel effect” discussed in depth in the “Industrial Canal Breach” section.

After Katrina, the breached parts were repaired with more suitable materials, and the earthen side levees were also armored with a combination of grass and riprap.

Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MR-GO)

St. Bernard Parish, located downriver from New Orleans, and geographically southeast of the city, is home primarily to white, lower- to middle-class homeowners. Virtually 100 percent of St. Bernard Parish went underwater during Hurricane Katrina.

The region, built along the naturally high ground along the Mississippi River, flooded in August 2005, mainly due to the Army Corps of Engineers’ inadequate maintenance of the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet, a little-used navigation channel.

Neighborhood in Chalmette, 10 miles south of New Orleans in St. Bernard Parish, along the Mississippi River. Photo/ Andy Levin CLICK TO ENLARGE

A little history: In 1940, New Orleans leaders dreamed of a navigation canal that flowed all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, making the city a “real” seaport. The intention was that this canal would shorten the distance from New Orleans to the Gulf from 120 miles to roughly 75 miles. The Army Corps predicted that the outlet would add $1.45 to the economy for each $1 of taxpayer money spent for its construction. Ultimately the project was approved and built by the Corps.

The MR-GO, which has been called as “straight as an engineer’s ruler,” begins just east of Interstate-510’s crossing of the GIWW east of New Orleans and takes a path south-southeast through the St. Bernard Parish wetlands just west of Lake Borgne to the Gulf of Mexico. On the day it opened in 1965, MR-GO was already nearly obsolete because it was too narrow and too shallow to provide for larger vessels. (The advantage of water transportation is greatest when cargo is the heaviest.) Furthermore, the straight design and lack of outward flow into the Gulf allowed the MR-GO to become “the perfect shortcut for salt-water intrusion,” which destroyed storm surge-buffering cypress forests and freshwater wetlands. Historically they had protected Orleans and St. Bernard Parishes during hurricane passages.

The channel was designed to have a surface width of 625 feet, bottom width of 500 feet and a 36-foot depth. But the Louisiana Ecosystem Restoration Study by the Army Corps in late year 2004 calculated that the ship traffic had caused the north bank of the channel to erode at a rate of 35 feet per year, leading to “the direct loss of approximately 100 acres of shoreline brackish marsh every year and the additional losses of interior wetlands and shallow ponds.” When Katrina arrived, the channel was up to 3,000 feet wide, a width that allowed waves up to nine feet on the MR-GO’s surface. These waves destroyed the levees, many even before the maximum surge had approached this location.

During Katrina, surge from the MR-GO and Lake Borgne rushed over the banks of the MR-GO, resulting in catastrophic flooding. The water advanced to St. Bernard Parish’s second line of defense, easily overtopping the 40-Arpent Canal’s levee and filling the entire parish with water to a height of 11.5 feet above sea level.

Katrina: Rear View Mirror. Cars were neatly deposited on the roofs of houses in Chalmette when the storm surge blasted through the community about 10 miles south of New Orleans///A street in Chalmette, Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina. Credit: Andy Levin CLICK TO ENLARGE

There was only one trial resulting from deaths related to the 2005 Flood–the trial of nursing home owners Sal and Mabel Mangano, charged with negligent homicide in the deaths of 35 elderly residents who perished in the quickly rising floodwater in the city of Violet. The couple had sheltered in place with the elderly residents, along with their extended family including two young grandsons, over concerns that the frail residents could not survive an evacuation. Besides, they reasoned, the area did not flood during Hurricane Betsy in 1965. To their shock, the nursing home flooded in minutes and the Mangano’s and their relatives struggled to save their charges.

The trial captivated the attention of the entire nation. On September 8, 2007, the jurors acquitted the Manganos largely because they were the only humans being blamed in the entire tragic episode of Hurricane Katrina and the levee breaches.

“There were a lot of mistakes made, and it should have been a lot of people answering for it,” said one juror, Kim Maxwell. “So why just these two people?”

According to Dr. Ivor van Heerden, leader of TEAM LOUISIANA, who testified at the trial, one very important reason for acquittal was that the trial strongly showed that the Corps was at fault for the flooding and deaths.

In June 2008, the Army Corps of Engineers New Orleans District submitted a Deep-Draft De-authorization Study of the MR-GO that stated, “An economic evaluation of channel navigation use does not demonstrate a Federal interest in continued operation and maintenance of the channel.” Congress ordered the MRGO closed as a direct result.

In November 2009, federal Judge Stanwood Duval ruled that the Corps’ mismanagement of maintenance at the MR-GO was directly responsible for flood damage in St. Bernard Parish and the Lower 9th Ward neighborhood after Katrina. The U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in March of 2012 that Duval was correct in his groundbreaking decision; however, the panel reversed its own decision six months later. The Corps was immune from damages because of a provision governing suits against the federal government that protects an agency when it makes a discretionary decision. Duval’s ruling included these statements:

“The Corps’ lassitude and failure to fulfill its duties resulted in a catastrophic loss of human life and property in unprecedented proportions.“

“The Corps’ negligence resulted in the wasting of millions of dollars in flood protection measures and billions of dollars in Congressional outlays to help this region recover from such a catastrophe. Certainly, Congress would never have meant to protect this kind of nonfeasance on the part of the very agency that is tasked with the protection of life and property.”

New Legislation that Changed America as We Know It

Though the levee breach event was not a shining moment for American civil engineering, it was a pivotal moment in American history. The nation took a different path due to the flooding event. The myriad changes to national policy as a result of this lynchpin moment include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nationwide assessment of levees;

Immediately after the Flood disaster, Congress directed the Army Corps of Engineers to conduct a nationwide assessment of levees built by the agency which had previously been turned over to local communities for operations and maintenance. The Corps, for the first time, identified and mapped all levees in the USACE program. More than 14,000 levee miles were identified as falling under its authority;

First-ever National Levee Safety Act;

Members of Congress made three attempts to attach levee-safety legislation to the Water Resources Development Act. The third attempt was H.R. 1495 and was called in short, the National Levee Safety Act of 2007. The legislation ordered the Secretary of the Army to administer several reforms and new programs. These included the creation of a

- database of both federal and non-federal levees,

- first-ever nationwide levee safety program,

- safety inspection tool using global positioning technology,

- sixteen member levee safety committee, and

- information to the public of the risks of living near levees.

National Flood Risk Management Program

In May 2006, the Army Corps of Engineers established the National Flood Risk Management Program for the purpose of integrating and synchronizing USACE flood risk management programs and activities both internally and with counterpart federal activities. The goals include:

- providing current accurate floodplain information to the public and decision makers,

- assessing flood hazards posed by aging flood damage reduction infrastructure, and

- public awareness and comprehension of flood hazards and risk.

In September 2007, the Corps of Engineers drafted and later issued new guidelines for inspecting and certifying federal levees, in Engineer Circular 1110-2-6067. The new guidelines stated there would no longer be grandfathering, exemptions and/or partial certifications. There must be a full and complete engineering analysis with a field inspection. Levee inspections were made more uniform across the nation to ensure compliance and now are required quarterly instead of annually.

Before August of 2005, there was usually only one type of levee inspection. These routine inspections, also called annual inspections, were a visual-only inspection to verify proper levee system operation and maintenance. The levee breaches in New Orleans demonstrated that these visual-only inspections could not always reveal design/and or construction problems deep underground. In response, the Army Corps began to require more risk-informed levee inspections and assessments including:

- continuous inspections by local sponsors with more rigorous standards and new checklists,

- annual robust inspections by Army Corps district offices that are professionally managed,

- periodic inspections and a screening assessment every five years, and

- risk assessments, a rigorous data intensive effort every ten years.

Reform of the Army Corps of Engineers

Congress also passed legislation impacting how the Army Corps of Engineers handles feasibility studies for levee improvements. The McCain-Feingold Corps Reform Amendment to the Water Resources Development Act of 2007 was passed by a narrow margin of 54-46 by the 109th Congress – 2nd Session. The law established clear triggers for review of costly (over $40 million) or controversial feasibility studies by an independent panel, gave panel members discretion to review whatever they deemed significant and imposed pressure to encourage the Corps to consider outside recommendations.

Changes in Levee Building by the Corps

Perhaps most important of all, changes were made to the way the Corps builds levees. In 2006, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Headquarters issued new guidance regarding deficiencies that were discovered in the design of I-walls in New Orleans. As described in Engineering Technical Letter ETL 1110-2-575,

“…These deficiencies centered on the phenomenon of a gap formed by flood loading between sheet pile and the soil on the flooded side of the wall. This gap contributed to several breaches of I-walls in New Orleans prior to their overtopping related to global stability or seepage….”

Working with the nation’s civil engineers, the Corps used the information gleaned from forensic investigations into levee and wall failures to rewrite the manuals used to build new structures worldwide, including incorporating a modern understanding of the risk of future hurricanes combined with the expected effects of global warming on sea-level rise in determining how high those structures should be built.

In addition to re-writing the standards for future levee-building, the Corps also took a hard look at I-walls nationwide and identified more than 50 I-wall levee projects with “potential performance concerns.” The Corps took steps to help levee districts nationwide evaluate and identify projects that may have a risk of poor performance.

Fifty-five percent of the American population lives in counties protected by levees. The changes to levee building and the scrutiny of levees already built both occurred due to the levee breach event in New Orleans. The 2005 levee breach event, a turning point, had the end result of making the majority of the American people safer from flooding.

New Legislation Passed in Louisiana

Before Katrina, five different levee districts operated as separate local sponsors for the federally-built flood protection in the greater New Orleans area. Soon after the levees broke in 2005, the presumption–made in haste in a complex environment–was that the commissioners of the OLB were not paying enough attention to flood protection and were therefore partly responsible for the flood disaster. So Congress, with relative speed, ordered the creation of a single state agency to be the local sponsor. Twelve million dollars for funding the federal levee investigation was withheld until this was done. In response, the state of Louisiana created the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), in act 8 of the First Extraordinary Session in 2005.

At about the same time, there was a separate local effort–spearheaded by the New Orleans Business Council–to pass legislation to create a new “super board” that would replace the five separate levee boards that governed the Greater New Orleans region. The legislation was intended to (1) remove distractions such as real estate management; (2) replace parochial flood control with regional flood control; and (3) require commissioners to have professional expertise, including hydrology, construction engineering and civil engineering.

Although a direct causal link between the actions of the pre-Katrina Orleans Levee Board and the breaching of the outfall drainage canals or other levees has not been established, few would disagree that a new form of levee board governance might be both necessary and beneficial for a major marine terminal like Greater New Orleans. In 2006, more than 80 percent of Louisiana residents who voted expressed their desire to enact legislation creating an empowered super-board. Ultimately, two levee board authorities were created, each of which had jurisdiction on opposite sides of the Mississippi River.

The historic levee board legislation put Louisiana on the frontier of good governance, as it became the first state in the nation to legislate such requirements. But the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authorities East and West would soon discover that their authority was limited. On June 19, 2014, at a meeting of the Authority-East, acting president Stephen Estopinal (and board member for more seven years) described the SLFPA-East as the “authority with no authority” and proceeded to describe a litany of examples where the Army Corps of Engineers ignored the concerns of the board. Three months later, John Barry would echo these sentiments in an interview with the New York Times magazine. Time will tell if the popular new form of levee board governance will play a meaningful role in keeping New Orleans’ residents safe from harm.

Lawsuits Filed Since the Flood

Numerous class action lawsuits were filed against the Army Corps of Engineers after Katrina. These were consolidated by federal Judge Stanwood Duval into two separate cases. The MR-GO (Mississippi River Gulf Outlet) lawsuit alleged that the Corps was negligent in its maintenance of the 76-mile shipping channel constructed by the agency in the mid-20th century. The suit alleged that the channel’s design and lack of outward flow into the Gulf allowed for salt-water intrusion, which damaged buffering cypress forests and wetlands that historically had protected New Orleans from storm surge. The MR-GO case included residents from the areas east of the Industrial Canal: New Orleans East, the Lower Ninth Ward, St. Bernard Parish and portions of the Upper Ninth Ward.

In September 2009, Judge Duval approved a $5 million settlement of a federal class-action lawsuit against the Orleans Levee District (OLD). It is instructive to note, however, that in a case such as this where the settlement money comes from insurance resulting from policies the OLD held on the levees, a settlement should not be considered evidence of wrongdoing. Insurance companies have a risk of being found in bad faith for refusing a bona fide settlement offer within or at policy limits. Explained more simply, if an insurer refuses to pay a proposed settlement, they could potentially become liable for the full amount of any future settlement or a judgment even if it exceeds their policy limits. The total damages claimed by the plaintiffs for the levee and flood wall failures were many billions of dollars. In this case, the insurer had the choice to pay $5 million or roll the dice and possibly end up bankrupt. The settlement reflects a legal strategy on the part of both defendants and plaintiffs.

In November 2009, Duval ruled that the Corps’ mismanagement of maintenance at the MR-GO was directly responsible for flood damage in St. Bernard Parish and the Lower 9th Ward after Katrina. The U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in March of 2012 that Duval was correct in his groundbreaking decision; however, the same panel reversed its own decision six months later. The Corps was immune from damages because of a provision governing suits against the federal government that protects an agency when it makes a discretionary decision. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the appeal.

The second case, commonly called the “LEVEE case,” included areas that flooded due to the outfall canal flood wall failures and also the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal failures. In January 2008, Judge Duval placed responsibility for the flood wall collapses of the 17th Street and London Avenue Canals and the resulting flooding in downtown New Orleans squarely on the Corps. However, the Corps could not be found financially liable due to sovereign immunity established by the Flood Control Act of 1928. Judge Duval wrote,

“The cruel irony here is that the Corps cast a blind eye, either as a result of executive directives or bureaucratic parsimony, to flooding caused by drainage needs and until otherwise directed by Congress, solely focused on flooding caused by storm surge. Nonetheless, damage caused by either type of flooding is ultimately borne by the same public fisc. Such egregious myopia is a caricature of bureaucratic inefficiency.”

Judge Duval dismissed the case, which has not been appealed.

MYTHBUSTERS!

Drive-by Pre-Katrina Levee Inspections

After Katrina, news stories reported that, “Annual levee inspections in Orleans Parish tended to be quick drive-by affairs ending with lunch for 40-60 people costing the state as much as $900.” This is true, but the same reports went on to suggest that the haphazard inspections might have contributed to the catastrophic flooding and that the Orleans Levee District might be partly responsible. Neither suggestion was ultimately borne out by the facts.

There may have been confusion regarding the definition of the word “inspection.” Pre-Katrina, the Army Corps was required to administer annual levee inspections of maintenance of federally built, flood protection works in Orleans Parish. These were termed “Inspections of Completed Works,” and were designed to ensure that the Orleans Levee District was complying with its federally mandated levee maintenance. The responsibility of the OLD was, and still is, mainly cutting the grass on levee embankments, removing unwanted vegetation and debris, and visually judging the surface manifestations of under seepage (most commonly associated with high flow conditions, during hurricanes and floods). The OLD also performed informal year-round “inspections” including, but not limited to, checking concrete surfaces on flood walls for open cracks and inspecting for ruts, depressions and erosion of their earthen levees.

Legal responsibility for the annual Inspection of Completed Works belongs to the Army Corps of Engineers. Going forward, the Corps’ inspections should perhaps be thought of as independent, once-per-year “quality audits” of the levee district’s year-round maintenance activities. Furthermore, as observed in the Chronology:

“…The annual inspections of levees and floodwalls involve visual verifications of local sponsors’ compliance with required maintenance; they do not, however, include the types of engineering assessments that would be needed to verify structure stability and performance…”

Every year, from 1959 to 2004, the Orleans Levee District received an award plaque with a grade of “Outstanding” for the “the manner in which the maintenance of its levees has been executed.” Photo/Sandy Rosenthal CLICK TO ENLARGE

There appears to be no evidence that improper maintenance on the part of the Orleans Levee District played a role in the failure of the 17th Street and London Avenue Canals. The inspections were considered of such minimal significance that the federally appointed authors of the “Decision-Making Chronology for the Lake Pontchartrain & Vicinity Hurricane Protection Project” (March 2008) relegated its discussion of them to appended text boxes. The reported pre-flood “drive-by levee inspections” are, therefore, irrelevant to questions of what caused the Flood.

Role of Environmentalists In The Decision Against The Barrier Plan

Between 1970 and 1975, the Corps developed a plan for sea gates for the region east of New Orleans that would prevent storm surge from flowing through Lake Borgne and into Lake Pontchartrain through two narrow channels at the Rigolets and Chef Menteur passes. The massive gates had embankment footprints up to 2,000 feet wide. Referred to as the Barrier Plan, it included a series of levees along the Pontchartrain lakefront and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, a navigable inland waterway. The gates would have allowed water to flow back and forth between the lakes, but would have been closed in advance of a hurricane. Note structures in map below depicted in green.

A group led by Luke Fontana filed lawsuit against the Barrier Plan in 1976 over the Corps’ cursory Environmental Impact Study (EIS). In Save our Wetlands vs. Rush, the plaintiffs claimed the Corps’ EIS did not meet the requirements of Section 102 of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), a federal law enacted in 1969.

Federal Judge Charles Schwartz agreed with Fontana and concluded that Save our Wetlands had proven their case. The court noted the EIS was based on obsolete data and that the Corps’ biological analysis “relied entirely on a single telephone conversation with a marine biologist.” To put this into perspective, the Corps’ final EIS, representing the entire environmental review of a multi-year, multimillion-dollar project, consisted of only four typewritten pages. Judge Schwartz issued an injunction preventing further progress on the barrier option until the Corps revised its EIS. He also wrote, however, that upon proper compliance with NEPA, “The injunction shall be dissolved and any hurricane plan thus properly presented will be allowed to proceed.”

In March 1978, the court lifted the injunction for all project elements except the barrier structures at Chef Menteur Pass, the Rigolets, and the Seabrook lock at the mouth of the IHNC. Ultimately, however, the Corps did not return with a more comprehensive EIS. In 1980, it completed a Draft Analysis of Alternative Plans, which concluded that higher levees providing hurricane protection were less costly, less damaging to the environment and also more acceptable to local interests.

Immediately after Katrina, the Corps’ abandonment of the Barrier Plan became the subject of politicians and journalists who alleged that environmentalists had blocked the Corps’ original plans for barrier structures and forced the agency to choose an alternate and inferior design that could not protect the city. The Barrier Plan was “stopped in its tracks,” claimed a Los Angeles Times, front-page news story.

Two law professors, Thomas McGarity and Douglas Kysar, in their article which highlighted the “hazards of hindsight analysis,” put the process under the microscope and found that subsequent to Judge Schwartz’s injunction, intense public opposition arose based on concerns for the environment, fears of increased flooding for people and property outside the barrier walls and distrust from citizens who believed the project was a “land grab” that would personally enrich some of the civic leaders. At this same time, costs were ballooning, caused by the factors of new design requirements and by general delay. As observed by Loyola Law Professor Robert Verchick (Harvard University Press, 2010),

“One can say that environmental concerns contributed to the political opposition and the litigation provided the information and the time for activists to organize. But at the same time, one must acknowledge that nothing prevented the Corps from acting more quickly to perform a sufficient environmental review and get the project approved. Had it believed that superior benefits of the option justified increased costs, it could surely have moved forward.”

There appears to be no documented evidence in the project record or any other indication that reveals that the Corps believed its switch from the Barrier Plan to the High Level Plan would increase the risk of flooding to New Orleans. In closing, as suggested by Kysar and McGarity, the initial belief that an environmental advocacy group doomed the city likely had its roots in hasty “hindsight analysis” made in the context of confusion immediately after Katrina.

Orleans Avenue Canal Spillway

The Orleans Avenue Canal’s levees were raised the same way the 17th Street and London Avenue Canals, but they did not breach. This was due, in part, to the presence of an unintended 100-foot long “spillway,” a section of wall significantly lower than the adjacent newer flood walls by Pump Station No. 7.

Immediately post-Katrina, the Orleans Levee Board took much criticism for the presence of this spillway located where eventual flood wall (I-wall) construction would require coordinated efforts between the OLB, the Sewerage & Water Board, the Department of Transportation & Development and, possibly, the Federal Highway Administration. Since this matter had not been resolved at the time of Hurricane Katrina’s arrival, floodwaters simply poured through the open gap, causing flooding to the city’s major public green space, adjacent City Park. This also served to partially relieve water levels within the canal.

In the photo below, it’s clear that the gap was significant at the Orleans Avenue Canal.

This inadvertent “spillway” (gap in the I-wall) was located under a viaduct carrying Interstate-610, where the top of the existing earthen levee crest lay approximately 5 to 6 feet below the tops of the adjacent concrete flood walls. Constructing a flood wall across this gap would involve driving steel sheet piling, in short segments, and splicing the short segments together under the freeway viaduct, all in accordance with state and federal transportation regulations. Completion of the flood wall would also have likely caused the brick walls of the old pump station to fail unless they had been significantly reinforced.

Had the canal walls of the 17th Street Canal and the London Avenue Canal not breached, this spillway could have allowed overtopping for several hours, resulting in significant, though not catastrophic, flooding. The OLB took much heat for this, even though responsibility was shared by at least three different organizations. In the end, of course, the failures of the 17th Street and London Avenue Canals made this issue moot.

Role of the Orleans Levee Board in the Failure of the 17th Street and London Avenue Canals

In the post-Flood environment of shock and confusion, a fairy tale took flight about a monster storm drowning a corrupted city that lay below sea level. A second story, repeated for years, was that the Army Corps was hamstrung by a politically connected levee board that “forced” the agency to build the inferior system that failed in August 2005. This exhibit separates the real from the fairy tale.

By 1981, the Army Corps began working out the engineering details to protect New Orleans from storm surges that could enter the city’s three main drainage canals–the 17th Street, London Avenue and Orleans Avenue Canals. This was necessary because the new, post-Hurricane Betsy design water levels were higher than most of the canals’ crests. The Corps eventually narrowed its recommendations to the two most cost-effective, which were 1) raising the height of the canals flood walls (parallel protection) or 2) installing gates at the canal mouths (frontage protection).

The Corps presented both plans, which it apparently considered equally effective, to the local sponsor (Orleans Levee Board). Meeting minutes from January 1988 to December 1991–critical years in the decision making–reveal that there were many additional meetings, entitled “Special Meetings,” devoted solely to discussions of flood protection. The voluminous meeting minutes show that the Engineering Committee asked the Corps many detailed questions.

The minutes also reveal that the OLB and the S&WB (Sewerage and Water Board) shared concerns over the Corps’ consideration of a prototype gate plan for self-actuating butterfly check valves, a gate plan which included no auxiliary pump stations like those constructed after Katrina. Both agencies viewed the gates-only plan as being incompatible with their interior drainage responsibilities and were concerned that when the gates were shut during a hurricane the pump stations would not be able to pump rainwater out of the city.

The OLB and the S&WB also questioned whether the untested prototype gates would always work properly during storms. The gates had already failed in a much-publicized model test attended by OLB members at the Corps’ Waterways Experiment Station (WES) in Vicksburg. As noted by Jed Horne in Breach of Faith (2006), it was an embarrassing moment for the Corps.

Post-Katrina investigations rightly observed that the adoption of “higher walls” protection for the outfall canals would significantly increase the number of miles of flood walls and other structures exposed to storm surges, thus increasing the probability that a storm surge could find a weak spot. However, in the 1990s this risk did not appear to have been recognized and/or communicated. On this issue, the Interagency Performance Evaluation Task Force (IPET), which was convened and managed by the Army Corps of Engineers after Katrina, observed:

“…A series of incremental decisions extending from the original ‘barrier’ plan to the ‘parallel protection’ structures ultimately constructed, systematically increased the inherent risk in the system without recognition or acknowledgment…”

From today’s vantage point, it appears the local sponsors were led to believe that the “higher walls” plan was technically equivalent to the “gates-no-pumps” plan, but was just more expensive. As observed by the authors of Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (DOTD) sponsored report Team Louisiana, led by coastal researcher Ivor van Heerden (2006), “They believed they had a right to pursue a more costly alternative if it would accomplish other purposes in addition to the hurricane protection objective.”

Apparently believing that both plans were equally effective, cost became the preeminent factor in the Corps’ consideration of “gates no pumps” versus “high walls” protection. The Corps considered it a congressional mandate to implement the least expensive alternative for providing the authorized project, assuming all of the choices to be adequately engineered.

Enormous pump station built at the 17th Street Canal’s mouth after the 2005 Flood. Photo/Heather Ruoss CLICK TO ENLARGE

Eventually, the Corps did recommend parallel protection for the 17th Street Canal. For reasons unique to this canal, there was no significant stated difference in the cost between the two approaches due to newly authorized sheet pile construction guidelines. Another reason noted in the project record was that the OLB and the S&WB preferred it.

However, for the much smaller capacity London and Orleans Avenue Canals, the Corps stood by its recommendation for the gates-no-pumps plan because it was significantly less expensive. The parallel protection plan was estimated in the 1980s to cost three times more than the gates plan for the London Avenue Canal and to cost five times more for the Orleans Avenue Canal.

In response, in 1988, the OLB began an aggressive push to find a way to convince the Corps to recommend the high walls plan for all three canals, not just the 17th Street. Then-OLB President Steven Medo hired a lobbyist named Bruce Feingerts to lead a legislative effort to push for getting the most federal aid participation possible to fund the parallel plan.

Regarding this attempt by the OLB to secure additional appropriations to fund the parallel plan, federally appointed water experts Douglas Woolley and Leonard Shabman (2008), authors of the “Decision Making Chronology,” would observe exactly 20 years later:

“…from the local perspective, the parallel protection plan was the best way to address both hurricane protection and interior drainage objectives and secure 70 percent federal funding toward those ends…”

Working with the support of the S&WB and neighborhood groups, Feingerts lobbied the Louisiana congressional delegation for the parallel plan for the Orleans and London Avenue Canals. Feingerts worked with U.S Representatives Robert Livingston, Lindy Boggs, and William Jefferson, and with U.S. Senator J. Bennett Johnston, Jr. toward that end. Neither Feingerts nor any member of the OLB lobbied specifically against the frontage plan. Their stated concern was that the gates, if installed without auxiliary pump stations, could cause massive flooding due to rainwater overtopping the walls.

Significant progress was made when Feingerts suggested to members of the Louisiana delegation that, in conferencing, they insert a ruling or language into an engrossed amendment of the approved version of the 1990 WRDA. The language redefined the Orleans and London Avenue Canals as part of the Hurricane Protection Project, which were, therefore, now a federal responsibility. The 1990 WRDA was signed by President George Bush and passed into law. The OLB had succeeded in getting the authorization for a project that they believed would keep people safe, but which would also reduce how much those same people had to contribute to the cost. Authorization for the funding and cost share soon followed.

A local affiliate of NBC TV televised a news story with anchorwoman Leslie Hill of WDSU on May 30, 1991, featuring triumphant OLB members and proud legislators stating that the Congressional delegation has done an “end run” on the Corps by slipping funding into an appropriations bill that would save taxpayers nearly $50 million. Senator Johnston was quoted as saying, “This will be the last piece as far as the 150,000 people living in this area, to protect these people who otherwise would not really be protected.” Not only was the superior project authorized in the opinions of the OLB Engineering Committee, but it was funded as well.

Fifteen years later, a Los Angeles Times article would lay blame for the outfall canal flood wall failures heavily on the OLB in light of the 1990 WRDA. The reporters for this Christmas Day, 2005 story described “a deft behind-the-scenes maneuver” by the OLB that forced the Corps to accept the higher flood walls. The article stated, “Corps engineers were openly peeved in 1990 when they learned about the Orleans board’s decision.”

But the Corps had not been caught by surprise. As previously established, the Corps had (1) already recommended the parallel plan for the 17th Street Canal, (2) was aware that the OLB preferred the same approach for the other two drainage canals,and (3) was aware that the OLB was compensating a lawyer to go to Washington DC to lobby for the parallel plan alternative.

It is clear there was some eleventh-hour maneuvering; however, this is pretty typical of how laws are passed in Washington, DC. Senator Johnston addressed this particular bit of “midnight magic” in the OLB meeting minutes on May 30, 1991:

“The more important things that are done, the things that touch people’s lives and pocketbooks, and the things that really measure the effectiveness of what Congress does as far as people in the State of Louisiana, are done quietly, and are done by virtue of knowing what you are doing or the position of power that you are in.”

During Hurricane Katrina, the raised canal walls of the 17th Street and London Avenue Canals failed at 50 percent of design loads. What is evident is that the Corps, in a separate attempt to limit project costs, had initiated a sheet pile load test (E-99 test) in the Atchafalaya Basin of Louisiana in the 1980s, but had misinterpreted the results and concluded that sheet piles only needed to be driven to depths of not more than 17 feet instead of between 31 and 46 feet. That decision saved approximately $100 million, but significantly reduced the overall reliability of the flood walls during the 2005 storm.

With regard to both the Corps’ initial recommendation to build the parallel plan for the 17th Street Canal, and to reduce the depths of the sheet pilings in the I-walls, there is no evidence that either the Corps or the OLB believed that risk would be significantly increased.

In 2015, J. David Rogers, co-chair of the Independent Levee Investigation Team sponsored by Univ. of California Berkeley, observed that “You cannot blame the Orleans Levee Board for pursuing a flood control option that the Corps itself proposed.”

Half of New Orleans is at or Well Above Sea Level

Contrary to popular perceptions, 50 percent of the city is at or well above sea level, according to an April 2007 report by Richard Campanella with the Center for Bioenvironmental Research.

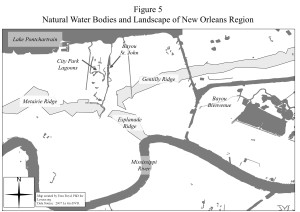

The highest regions include the natural high ground along the Mississippi River created by flooding over thousands of years. Also on high ground are neighborhoods built atop and along “ridges” that are ancient former banks of rivers and/or bayous. A road, originally “Gentilly Road,” was built on the ridge, and formed the eastern path into the oldest part of the city.

On the at-and-above sea level list are the New Orleans neighborhoods of greater Carrollton, River Bend, Audubon, University, Uptown, the Garden District, Lower Garden District, Irish Channel, the French Quarter, Treme, Bayou St. John, the Marigny, Bywater, Holy Cross, Algiers Point, McDonogh, Lakeshore, Lake Vista, Lake Terrace and Lake Oaks. Add to that the Warehouse and Central Business Districts, portions of the 6th and 7th wards, Central City and Mid-City as well as areas along Gentilly Boulevard and Chef Menteur Highway in eastern New Orleans and terrain along the Mississippi River in Algiers, City Park Avenue and the Fair Grounds area.

Mosaic is color-coded to show areas above sea level in brown fading to yellow then green. Areas below sea level are blue. with the lowest points in dark blue. The map above was created by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration using LIDAR Light Detection and Ranging, a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser to measure ranges (variable distances) to the Earth.

The Evacuation of New Orleans for Katrina

Possibly the most ingrained image from the days after Hurricane Katrina struck may be that of exhausted and desperate people at the New Orleans Superdome and Convention Center, trapped in the city after the levees broke. These searing images have resulted, naturally, in a belief that state and local officials were negligent in pre-arranging for evacuation of the city’s residents before Katrina arrived. This is not completely true, and the explanation begins with the story of Hurricane Ivan one year before.

“HELP US, PLEASE”

Angela Perkins almost slipped away a couple of times. She grabbed Brett Duke and me from the beginning. She was our entree into the New Orleans Convention Center. As she got distracted, I kept calling her back. She was passionate yet on the verge of hopelessness. As she frantically darted from one scene to another, she suddenly began pleading to the world through our lenses as she dropped to her knees and shrieked, ÒHelp Us, Please!Ó A short time later, fighting back tears, Brett put his arm around my shoulder and pulled me close.Can we pray? CLICK TO ENLARGE

Ivan wasn’t remembered for its ferocity, but rather the name became synonymous with state government incompetence. That was the very first year that the concept of contraflow was introduced in Louisiana. The basic idea behind contraflow is turning all lanes of the interstate and the Causeway Bridge over Lake Pontchartrain into one-way roads, with all lanes outbound from the city. The concept is simple and ingenious, but the devil is in the details. The maneuver requires pristine coordination between the different parish governments and the state police.

During that trial first year to evacuate residents for Ivan, contraflow was very limited due to state police concerns about the large number of staff required to close exits. Over half of New Orleans residents evacuated in advance of Ivan causing traffic delays of up to 12 hours, and up to 20 hours for those evacuating to Texas. Many turned around and went back home to watch Ivan sputter and weaken to a tropical storm.

Two days before Hurricane Katrina, one year later, appeals to evacuate were repeated over and over on radio and television, and continued throughout the day. Plaquemines and St. Charles Parishes, coastal parishes south of New Orleans, ordered mandatory evacuations, and Governor Blanco ordered contraflow to take effect. By 4 p.m. on Saturday, the state police had reversed all inbound lanes and full contraflow began.

Another key to contraflow is the phased evacuations 50 hours in advance in Louisiana’s lowest-lying parishes like Plaquemines, and 30 hours in advance for the New Orleans metropolitan area. The improved contraflow resulted in only two-three hour delays. But were it not for the “dry run” of Hurricane Ivan in 2004, thousands might have abandoned their attempt to evacuate for the 2005 hurricane and instead turn around and gone back home.

In hindsight analysis, not nearly enough planning was directed toward those without a car, credit cards, road experience and a network of family and friends elsewhere. Many, especially the elderly, stayed to care for their pets and perished with them.

Despite these significant shortcomings, years later, it was unilaterally agreed upon that Hurricane Ivan saved a lot of lives because the September 2004 storm exposed a contraflow plan badly in need of revision. Furthermore, Governor Blanco’s evacuation of 93 percent of the New Orleans region in August 2005 using contraflow would be cited as the most successful rapid evacuation of a major city in American history.

The displacement of New Orleanians before and after Hurricane Katrina also represents the largest mass migration in United States since the Civil War. (p. 44, ERP)